Scaling Transactions from a Single Account

Flow is designed for consumer-scale internet applications and is one of the fastest blockchains globally. Transaction traffic on deployed contracts can be divided into two main categories:

-

User Transactions

These are transactions initiated by users, such as:

- Buying or selling NFTs

- Transferring tokens

- Swapping tokens on decentralized exchanges (DEXs)

- Staking or unstaking tokens

In this category, each transaction originates from a unique account and is sent to the Flow network from a different machine. Developers don’t need to take special measures to scale for this category, beyond ensuring their logic is primarily on-chain and their supporting systems (e.g., frontend, backend) can handle scaling if they become bottlenecks. Flow’s protocol inherently manages scaling for user transactions.

-

System Transactions

These are transactions initiated by an app’s backend or various tools, such as:

- Minting thousands of tokens from a single minter account

- Creating transaction workers for custodians

- Running maintenance jobs and batch operations

In this category, many transactions originate from the same account and are sent to the Flow network from the same machine, which can make scaling tricky. This guide focuses on strategies for scaling transactions from a single account.

In the following sections, we’ll explore how to execute concurrent transactions from a single account on Flow using multiple proposer keys.

This guide is specific to non-EVM transactions. For EVM-compatible transactions, you can use any EVM-compatible scaling strategy.

Problem

Blockchains use sequence numbers, also known as nonces, for each transaction to prevent replay attacks and allow users to specify the order of their transactions. The Flow network requires a specific sequence number for each incoming transaction and will reject any transaction where the sequence number does not exactly match the expected next value.

This behavior presents a challenge for scaling, as sending multiple transactions does not guarantee that they will be executed in the order they were sent. This is a fundamental aspect of Flow’s resistance to MEV (Maximal Extractable Value), as transaction ordering is randomized within each block.

If a transaction arrives out of order, the network will reject it and return an error message similar to the following:

_10* checking sequence number failed: [Error Code: 1007] invalid proposal key: public key X on account 123 has sequence number 7, but given 6

Our objective is to execute multiple concurrent transactions without encountering the sequence number error described above. While designing a solution, we must consider the following key factors:

-

Reliability

Ideally, we want to avoid local sequence number management, as it is error-prone. In a local sequence number implementation, the sender must determine which error types increment the sequence number and which do not. For instance, network issues do not increment the sequence number, but application errors do. Furthermore, if the sender's sequence number becomes unsynchronized with the network, multiple transactions may fail.

The most reliable approach to managing sequence numbers is to query the network for the latest sequence number before signing and sending each transaction.

-

Scalability

Allowing multiple workers to manage the same sequence number can introduce coupling and synchronization challenges. To address this, we aim to decouple workers so that they can operate independently without interfering with one another.

-

Capacity Management

To ensure reliability, the system must recognize when it has reached capacity. Additional transactions should be queued and executed once there is sufficient throughput. Fire-and-forget strategies are unreliable for handling arbitrary traffic, as they do not account for system capacity.

Solution

Flow's transaction model introduces a unique role called the proposer. Each Flow transaction is signed by three roles: authorizer, proposer, and payer. The proposer key determines the sequence number for the transaction, effectively decoupling sequence number management from the authorizer and enabling independent scaling. You can learn more about this concept here.

We can leverage this model to design an ideal system transaction architecture as follows:

-

Multiple Proposer Keys

Flow accounts can have multiple keys. By assigning a unique proposer key to each worker, each worker can independently manage its own sequence number without interference from others.

-

Sequence Number Management

Each worker ensures it uses the correct sequence number by fetching the latest sequence number from the network. Since workers operate with different proposer keys, there are no conflicts or synchronization issues.

-

Queue and Processing Workflow

- Each worker picks a transaction request from the incoming requests queue, signs it with its assigned proposer key, and submits it to the network.

- The worker remains occupied until the transaction is finalized by the network.

- If all workers are busy, the incoming requests queue holds additional requests until there is enough capacity to process them.

-

Key Reuse for Optimization

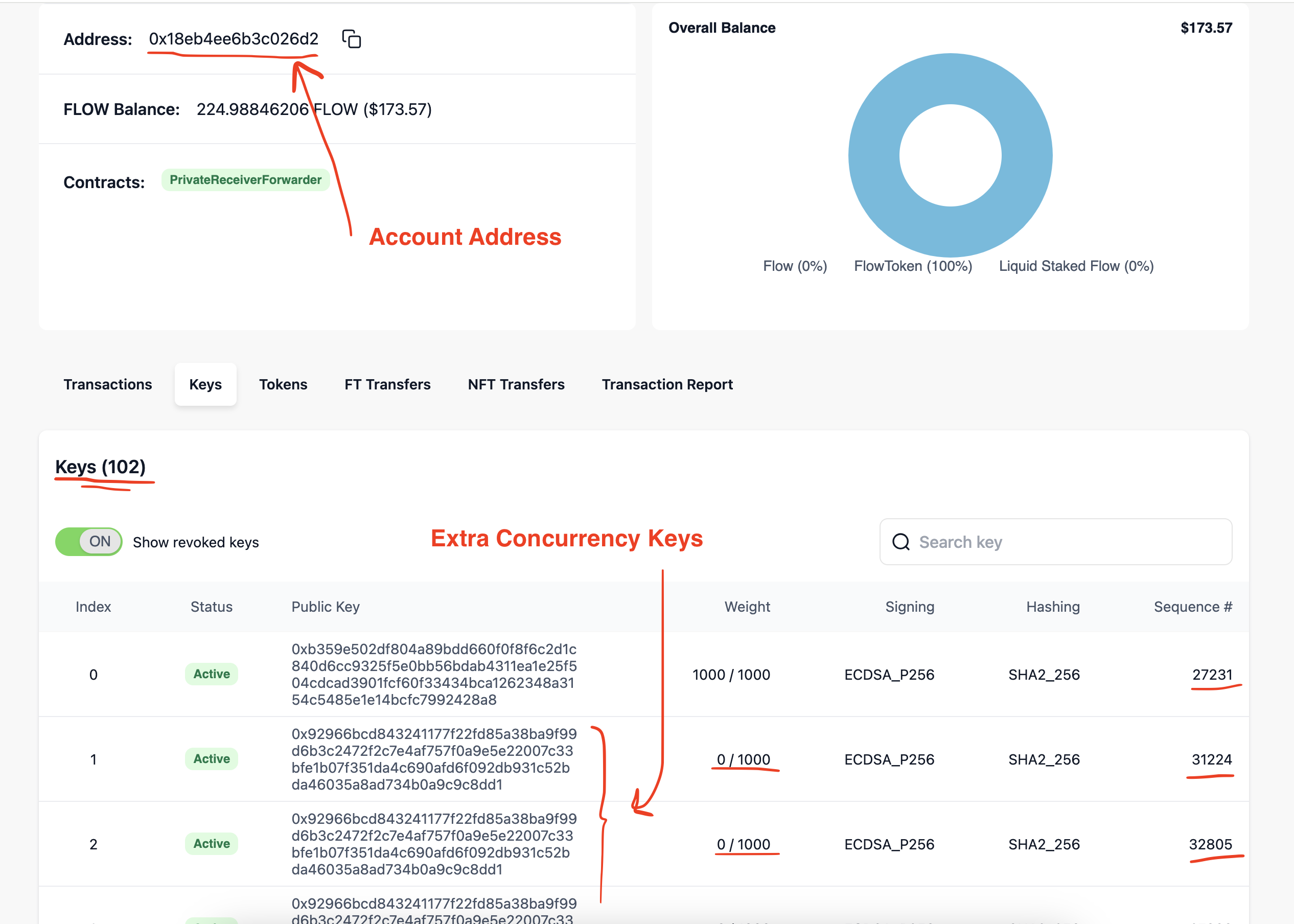

To simplify the system further, we can reuse the same cryptographic key multiple times within the same account by adding it as a new key. These additional keys can have a weight of 0 since they do not need to authorize transactions.

Here’s a visual example of how such an account configuration might look:

As shown, the account includes additional weightless keys designated for proposals, each with its own independent sequence number. This setup ensures that multiple workers can operate concurrently without conflicts or synchronization issues.

In the next section, we’ll demonstrate how to implement this architecture using the Go SDK.

Example Implementation

An example implementation of this architecture can be found in the Go SDK Example.

This example deploys a simple Counter contract:

_16access(all) contract Counter {_16_16 access(self) var count: Int_16_16 init() {_16 self.count = 0_16 }_16_16 access(all) fun increase() {_16 self.count = self.count + 1_16 }_16_16 access(all) view fun getCount(): Int {_16 return self.count_16 }_16}

The goal is to invoke the increase() function 420 times concurrently from a single account. By adding 420 concurrency keys and using 420 workers, all these transactions can be executed almost simultaneously.

Prerequisites

We're using Testnet to demonstrate real network conditions. To run this example, you need to create a new testnet account. Start by generating a key pair:

_10flow keys generate

You can use the generated key with the faucet to create a testnet account. Update the corresponding variables in the main.go file:

_10const PRIVATE_KEY = "123"_10const ACCOUNT_ADDRESS = "0x123"

Code Walkthrough

When the example starts, it will deploy the Counter contract to the account and add 420 proposer keys with the following transaction:

_20transaction(code: String, numKeys: Int) {_20_20 prepare(signer: auth(AddContract, AddKey) &Account) {_20 // deploy the contract_20 signer.contracts.add(name: "Counter", code: code.decodeHex())_20_20 // copy the main key with 0 weight multiple times_20 // to create the required number of keys_20 let key = signer.keys.get(keyIndex: 0)!_20 var count: Int = 0_20 while count < numKeys {_20 signer.keys.add(_20 publicKey: key.publicKey,_20 hashAlgorithm: key.hashAlgorithm,_20 weight: 0.0_20 )_20 count = count + 1_20 }_20 }_20}

Next, the main loop starts. Each worker will process a transaction request from the queue and execute it. Here’s the code for the main loop:

_36// populate the job channel with the number of transactions to execute_36txChan := make(chan int, numTxs)_36for i := 0; i < numTxs; i++ {_36 txChan <- i_36}_36_36startTime := time.Now()_36_36var wg sync.WaitGroup_36// start the workers_36for i := 0; i < numProposalKeys; i++ {_36 wg.Add(1)_36_36 // worker code_36 // this will run in parallel for each proposal key_36 go func(keyIndex int) {_36 defer wg.Done()_36_36 // consume the job channel_36 for range txChan {_36 fmt.Printf("[Worker %d] executing transaction\n", keyIndex)_36_36 // execute the transaction_36 err := IncreaseCounter(ctx, flowClient, account, signer, keyIndex)_36 if err != nil {_36 fmt.Printf("[Worker %d] Error: %v\n", keyIndex, err)_36 return_36 }_36 }_36 }(i)_36}_36_36close(txChan)_36_36// wait for all workers to finish_36wg.Wait()

The IncreaseCounter function calls the increase() function on the Counter contract:

_30// Increase the counter by 1 by running a transaction using the given proposal key_30func IncreaseCounter(ctx context.Context, flowClient *grpc.Client, account *flow.Account, signer crypto.Signer, proposalKeyIndex int) error {_30 script := []byte(fmt.Sprintf(`_30 import Counter from 0x%s_30_30 transaction() {_30 prepare(signer: &Account) {_30 Counter.increase()_30 }_30 }_30_30 `, account.Address.String()))_30_30 tx := flow.NewTransaction()._30 SetScript(script)._30 AddAuthorizer(account.Address)_30_30 // get the latest account state including the sequence number_30 account, err := flowClient.GetAccount(ctx, flow.HexToAddress(account.Address.String()))_30 if err != nil {_30 return err_30 }_30 tx.SetProposalKey(_30 account.Address,_30 account.Keys[proposalKeyIndex].Index,_30 account.Keys[proposalKeyIndex].SequenceNumber,_30 )_30_30 return RunTransaction(ctx, flowClient, account, signer, tx)_30}

The above code is executed concurrently by each worker. Since each worker operates with a unique proposer key, there are no conflicts or synchronization issues. Each worker independently manages its sequence number, ensuring smooth execution of all transactions.

Finally, the RunTransaction function serves as a helper utility to send transactions to the network and wait for them to be finalized. It is important to note that the proposer key sequence number is set within the IncreaseCounter function before calling RunTransaction.

_26// Run a transaction and wait for it to be sealed. Note that this function does not set the proposal key._26func RunTransaction(ctx context.Context, flowClient *grpc.Client, account *flow.Account, signer crypto.Signer, tx *flow.Transaction) error {_26 latestBlock, err := flowClient.GetLatestBlock(ctx, true)_26 if err != nil {_26 return err_26 }_26 tx.SetReferenceBlockID(latestBlock.ID)_26 tx.SetPayer(account.Address)_26_26 err = SignTransaction(ctx, flowClient, account, signer, tx)_26 if err != nil {_26 return err_26 }_26_26 err = flowClient.SendTransaction(ctx, *tx)_26 if err != nil {_26 return err_26 }_26_26 txRes := examples.WaitForSeal(ctx, flowClient, tx.ID())_26 if txRes.Error != nil {_26 return txRes.Error_26 }_26_26 return nil_26}

Running the Example

Running the example will execute 420 transactions at the same time:

_10→ cd ./examples_10→ go run ./transaction_scaling/main.go_10._10._10._10Final Counter: 420_10✅ Done! 420 transactions executed in 11.695372059s

It takes roughly the time of 1 transaction to run all 420 without any errors.